What is Bird Banding and Why is it Useful?

Posted:

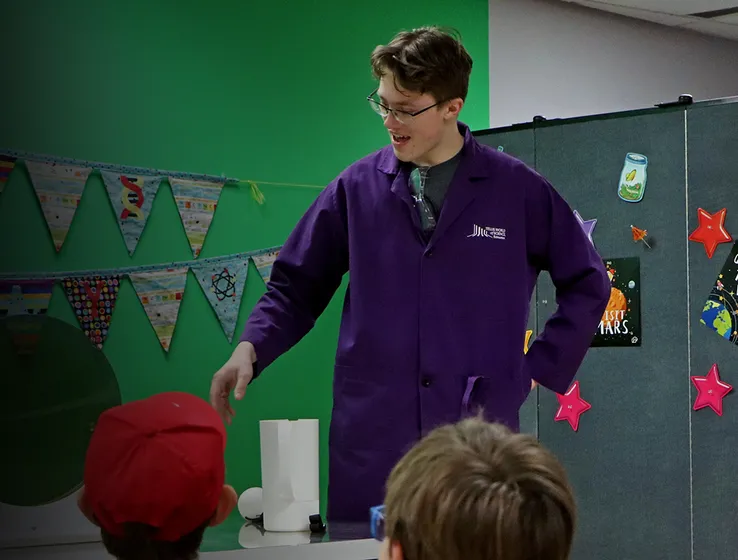

Written by: Jenny Niemi, Science Presenter

In 1977, an injured Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) was turned into a wildlife rescue in New York state. The blackbird, which was 15 years and 9 months old upon intake, was rehabilitated and later released. This individual is the oldest wild Red-winged Blackbird ever recorded. How did the wildlife rescue know that this blackbird was almost 16 years old and how do scientists know how long animals live in the wild?

Bird legs with a leg band on each leg. Photo by Brian Smucker, CC (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en)

This Red-winged Blackbird, like over 65 million other birds in North America, was marked with an aluminum bracelet called a “leg band”. Leg bands have a registration number stamped into the metal and are put on birds by specially trained banders who know how to attach the band securely without causing injury to the bird. Each bird band is registered and information about the bird’s approximate age, size, weight, sex, and condition are recorded into a centralized database.

Bald Eagle with aluminum leg band

If you find a bird with a band that you can read, you can report the number here. Sometimes, you may need help to read the band and using binoculars or a camera can help! If you still can’t read the number on the bird band, don’t worry – there is no need to chase the birds, as banding stations might recapture the bird during its next migration. If you see a pet bird (for example a parrot or racing pigeon) that does not belong in the wild, they may also have bands that will help reunite them with their family.

Leg bands are just one way that scientists can keep track of individuals. Scientists may use other low-technology visual marks (neck bands, ear tags, paint marks, scars) to identify individuals in a population, but high-tech options are available to monitor migration (GPS collars on larger mammals) or feeder and nest box use. Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) and Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT; an implanted microchip) are being used to study Purple Martins and their nesting habitats, and you can read more about that here.

Now we know some of the information scientists learn from bird banding, and some alternative methods of keeping track of individual animals for different types of studies. The type of study we’ll be focusing on for the rest of this article is a mark-and-recapture study. This study lets you mark an individual, release them back to nature, and then try to recapture them. In birds, this may be catching them at a bird banding station, marking them with a bird band, releasing them to continue on their migration, and recapturing them at a bird banding station at another time.

So far, we’ve talked about bird banding and GPS studies for tracking migration. But mark-and-recapture studies also have another purpose. We can estimate the population based on the number of individuals we mark and then recapture. Here is a fun activity that you can do to learn how scientists conduct this research.

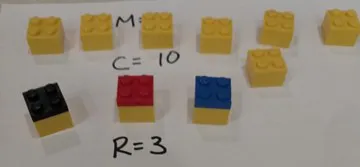

Activity: Mark-and-Recapture with LEGO

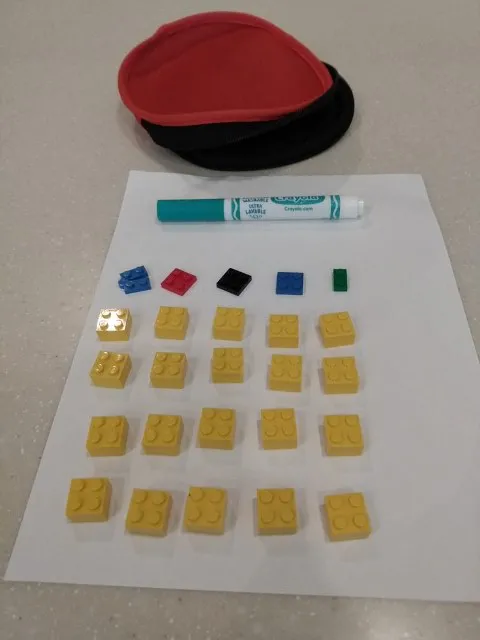

You will need:

- 20 standard LEGO blocks

- 5 flat LEGO blocks

- A bag

- A calculator, pencil, and notepad

For our experiment, we’re going to know the population of our LEGO. We are going to have 20 LEGO pieces. If you don’t have LEGO, you can use paper ripped into 20 pieces and folded in half to make it easier to grab. If you’re using paper, mark the captured paper by placing an X on one side.

- Place your 20 standard LEGO (or paper) pieces into a bag and shake the bag.

- Capture 5 pieces of LEGO.

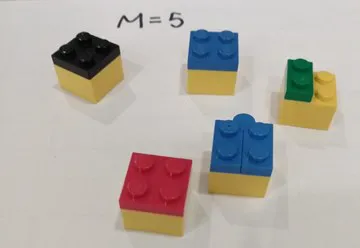

- Mark your captured LEGO by attaching a flat LEGO piece. On your notepad, write Marked = 5 (or however many you marked).

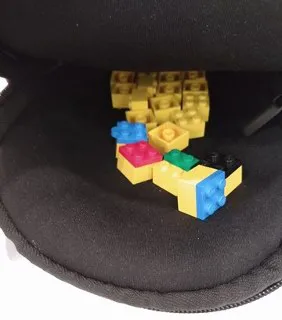

4. Release your LEGO back into the bag. Shake the bag to disperse the marked individuals into your population.

5. Capture a handful of LEGO. To make the example math easier, I am going to capture 10 pieces of LEGO, but in a real experiment you may end up with any number (even 0!) of subjects captured.

On your notepad, write Captured = 10 (or however many you caught)

6. Count the number of individuals who were marked. This number on the first round could be from 0 to 5.

On your notepad, write Recaptured = #. I recaptured 3, so I will write Recaptured = 3.

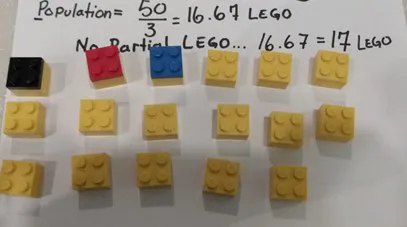

7. Use your calculator to estimate your population size. Always round up to the next whole number.

Population Size = (Marked x Captured) / Recaptured

Population Size = (5 x 10)/3

Population Size = 50/3 = 16.67 or 17 individuals.

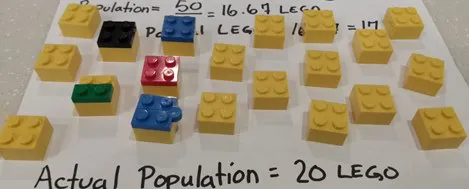

Hmm... according to my mark-and-recapture study the total population of LEGO is 17. Let’s dump out the bag and double check that our math is right... I still have 20 individuals, 5 of whom are marked. What happened? Was I wrong? Not exactly...

Mark-and-recapture is a sampling method. We use samples when we can’t count every single individual. If we take multiple samples (Repeat steps 4-7), we can calculate the average number of individuals. Over time and lots of experiments, we should end up close to the true population. Imagine counting every Red-Winged Blackbird in Canada! They move around far too much for that to be accurate and there are too many of them for this to be easy.

Scientists use mark-and-recapture studies to track movements of individuals, species abundance (number of each species present), and species diversity (number of different species). Mark-and-recapture studies work best with smaller populations as you’re more likely to recapture your marked individuals. If you have a really large population or range, you need to mark more individuals. Imagine a bag with 100 LEGO and only 5 marked pieces!

With Red-Winged Blackbirds, we can find out how old an individual is based on when it was first banded, we can possibly learn where it overwinters, migrates, and nests (if it’s caught at bird stations), and we can estimate the population (abundance), and population trend (increases and decreases) of Red-Winged Blackbirds based on the number captured and recaptured each year!

Spring is flying by, and with the bird observatories busy banding birds, it’s time for the Alberta Biomonitoring Institute’s (ABMI) BiodiverCITY challenge. Armed with the NatureLynx app, become a Citizen Scientist as you photograph Edmonton’s plants, animals, insects, and birds – you might even see a bird with a leg band! The BiodiverCITY Challenge runs from June 10th to 13th, 2021.

Related Articles

Guest post - Nahanni National Park Reserve - Kathryn Walpole

In a series of three blog posts, we are delighted to partner with Parks Canada to introduce you to three National Parks and three of the amazing women of STEM who are working together to meet the challenge of protecting these special places for present and future generations.

Why I Became A Psychologist Who Studies Animals

A guest post by Dr. Lauren Guillette, TWOSE Science Fellow, for Science Literacy Week 2020. Lauren discusses why she became a psychologist who studies animals and her favourite science books.

Be Very, Very Quiet...

This week we are celebrating Science Literacy Week all across Canada! The theme this year is biodiversity, an excellent opportunity for Nature Exchange to explore a new part of nature. To celebrate, I examined some of the biodiversity within The TELUS World of Science Centre - Edmonton's backyard (otherwise known as Coronation Park). Some organisms were easy to find but others were much, much harder.

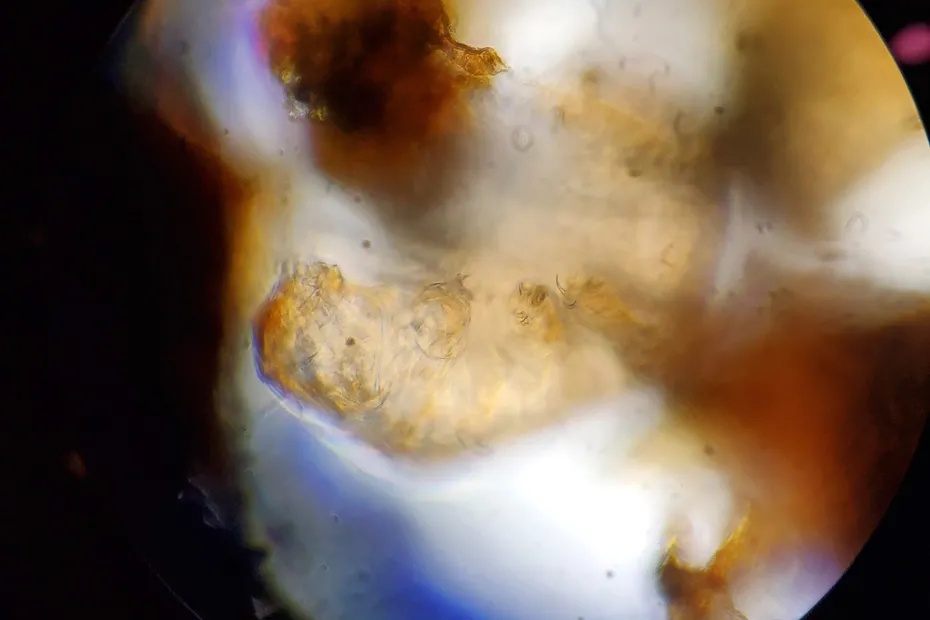

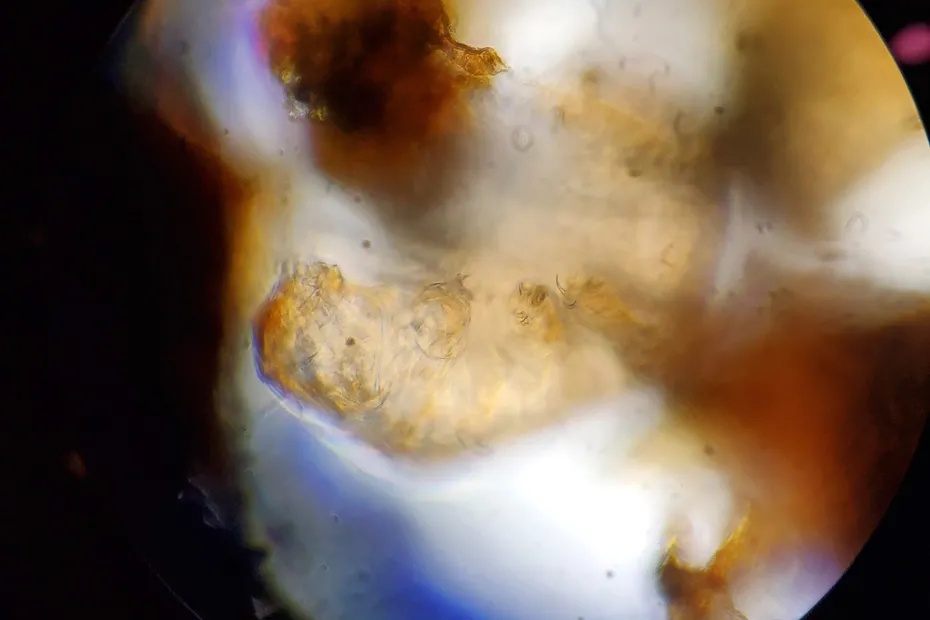

One of the most plentiful, and hardest to find, is the microscopic master of disguise, the tardigrade.

Related Articles

Guest post - Nahanni National Park Reserve - Kathryn Walpole

In a series of three blog posts, we are delighted to partner with Parks Canada to introduce you to three National Parks and three of the amazing women of STEM who are working together to meet the challenge of protecting these special places for present and future generations.

Why I Became A Psychologist Who Studies Animals

A guest post by Dr. Lauren Guillette, TWOSE Science Fellow, for Science Literacy Week 2020. Lauren discusses why she became a psychologist who studies animals and her favourite science books.

Be Very, Very Quiet...

This week we are celebrating Science Literacy Week all across Canada! The theme this year is biodiversity, an excellent opportunity for Nature Exchange to explore a new part of nature. To celebrate, I examined some of the biodiversity within The TELUS World of Science Centre - Edmonton's backyard (otherwise known as Coronation Park). Some organisms were easy to find but others were much, much harder.

One of the most plentiful, and hardest to find, is the microscopic master of disguise, the tardigrade.